Inventory Valuation Techniques: A Practical Guide to Choosing Methods

Discover inventory valuation techniques like FIFO, LIFO, and WAC, and learn how to choose the right method for accurate financial reporting.

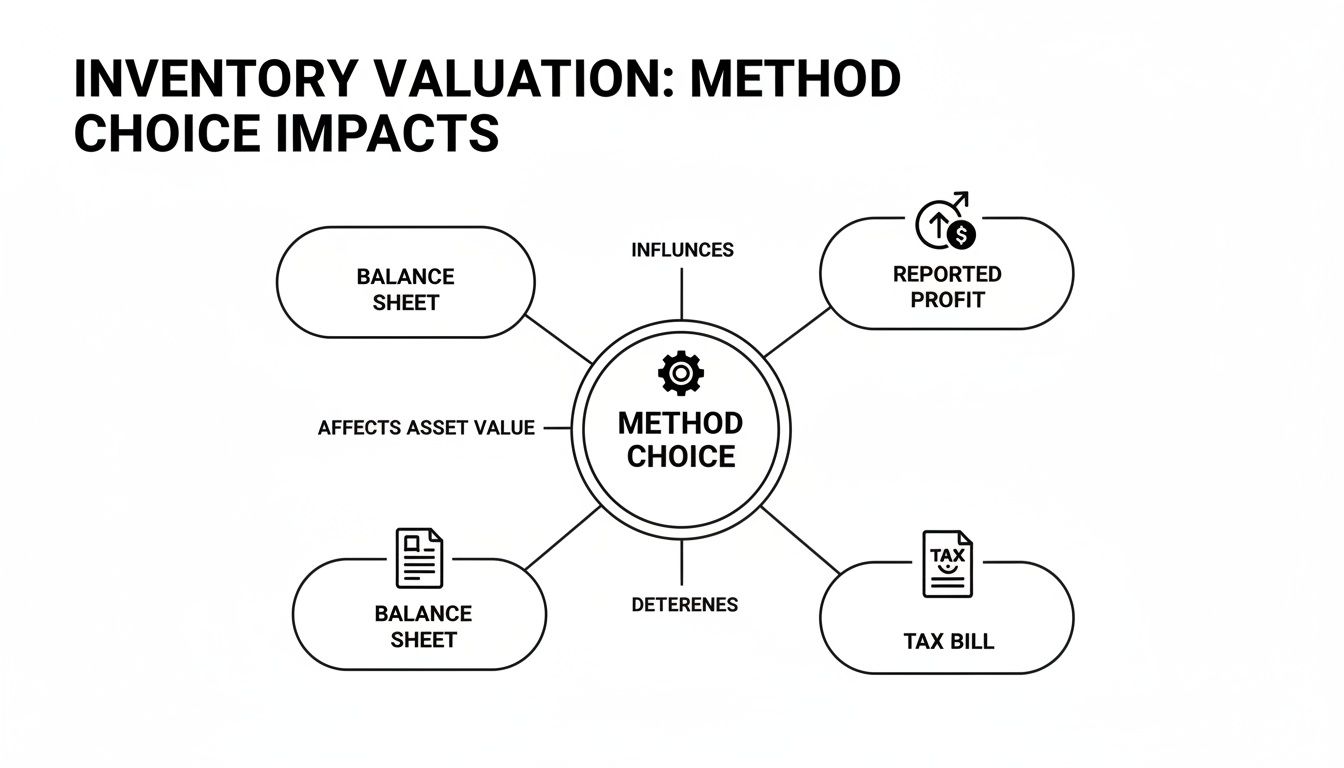

Inventory valuation isn't just an accounting headache—it's a strategic decision that shapes your company's financial story. The method you pick directly impacts your reported profit, tax liability, and balance sheet, telling a very different tale about your company's performance.

Why Your Inventory Valuation Method Matters

Choosing how to value your inventory is a lot like choosing which lens to put on a camera. The subject—your company's financial health—stays the same, but the picture you present can look dramatically different. This choice has real-world consequences, affecting everything from how much tax you pay to how investors and lenders see your operational efficiency.

Think about it from our perspective at Wolverine Assemblies. We buy steel coils all the time, and the price is always changing. When we sell finished parts made from that steel, which cost do we use for the sale? The cost of the first coil we bought months ago, or the cost of the most recent, more expensive one? The answer completely changes our Cost of Goods Sold (COGS).

That single decision sends ripples across your entire financial reporting.

Connecting Shelf Value to Bottom Line Profit

A higher COGS means lower reported gross profit, which can actually lower your taxable income. On the other hand, a lower COGS pumps up your reported profit, making your company look more attractive to lenders and stakeholders. Your choice of inventory valuation techniques ensures your financial statements are not just compliant, but also smart.

The stakes are high, and the difference is clear in global accounting standards. FIFO (First-In, First-Out) is the go-to method for most of the world. Why? Because International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), used in over 140 countries, don't allow LIFO (Last-In, First-Out).

Meanwhile, U.S. GAAP still gives LIFO the green light, which has historically helped American companies reduce their tax bills during inflationary times. This split means that when prices are rising, a U.S. company using FIFO might report net income that is 5–15 percentage points higher than a competitor using LIFO—a huge reporting gap. You can get a closer look at how these methods work in this in-depth inventory valuation guide.

Your valuation method isn't just a formula; it's a communication tool. It tells a story to tax authorities, investors, and your own team about how well you manage costs and turn assets into profit.

Getting a handle on these methods is fundamental. It gives you the power to:

- Manage Tax Liability: Intelligently lower your taxable income when costs are on the rise.

- Improve Financial Reporting: Show a stronger balance sheet to attract investment or get better loan terms.

- Enhance Decision-Making: Get a clearer view of your true profitability and operational costs.

Before we jump into the math, it’s crucial to get this one thing straight: your inventory valuation method is one of the most powerful levers you can pull in financial management.

Exploring The Core Inventory Valuation Techniques

Picking the right inventory valuation technique feels a lot like choosing the right tool for a specific job on the factory floor. You wouldn't use a hammer to turn a screw, right? In the same way, the method you select—FIFO, LIFO, Weighted Average, or Specific Identification—needs to line up with your operational reality and financial goals.

Let's break down these core methods.

Think of your inventory not just as a number on a spreadsheet but as a physical system. Each valuation method makes a different assumption about which costs leave the shelf first when you make a sale. This "cost flow assumption" is the heart of the whole process.

The choice you make here has a direct and significant impact on your company's financial story. As the diagram below shows, your selected method influences everything from your reported profit and tax bill to the strength of your balance sheet.

This makes it clear: your valuation method is a central gear in your financial machine, driving the results on your most critical reports.

For a clearer picture, here’s a quick rundown of how these four methods stack up against each other.

A Quick Comparison of Inventory Valuation Methods

This table summarizes the core principle of each technique and where it fits best.

As you can see, there’s no single "best" method—only the one that’s best for your specific inventory and business strategy.

FIFO: The First-In, First-Out Method

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method is the most straightforward and widely used of the bunch. It runs on a simple, logical principle: the first items you buy are the first ones you assume you’ve sold.

Think of the milk section at the grocery store. The staff always pushes the older cartons to the front. When you grab one, you’re taking the oldest stock first. That’s FIFO in action. For a manufacturer, this means the cost of the earliest raw materials purchased gets assigned to the first finished goods sold.

This approach lines up perfectly with the natural physical flow of many goods, especially anything perishable or technology that becomes outdated.

During periods of rising prices (inflation), FIFO results in a lower Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) because you're matching older, cheaper costs against current revenue.

By assigning older costs to COGS, FIFO often leads to higher reported net income and a higher ending inventory value on the balance sheet. This can make a company appear more profitable and financially stable to lenders and investors.

The trade-off? That higher reported profit also means a higher tax liability. It’s a direct choice between financial appearance and cash flow.

LIFO: The Last-In, First-Out Method

Now, let's flip that idea on its head. The Last-In, First-Out (LIFO) method assumes the most recently purchased items are the first ones sold. This technique is unique to U.S. GAAP and is not permitted under international standards (IFRS).

The best analogy for LIFO is a pile of coal or sand. A new truckload gets dumped on top of the pile. When you need some, you scoop it from the top—the last material that came in.

Under LIFO, your COGS reflects the most recent, and often highest, costs. This is a big deal during inflationary periods.

- Impact on COGS: It matches your most current costs with current revenues, giving a more realistic picture of your present-day profit margins.

- Tax Implications: By increasing COGS, LIFO reduces your reported net income. This can result in a lower tax bill, and that tax deferral is the main reason companies choose LIFO.

While it's great for tax planning, LIFO can make your balance sheet look a little strange. The remaining inventory value is based on older, potentially ancient costs, which can seriously understate the true value of your assets.

Weighted Average Cost And Specific Identification

What if your inventory items are all mixed together and you can't tell one batch from another? That’s where the Weighted Average Cost (WAC) method comes in. This approach smooths out cost fluctuations by calculating a single average cost for all available units.

Picture a gas station's huge underground storage tank. When a new fuel delivery arrives, it mixes right in with the fuel already there. The cost of the gas you pump into your car isn't tied to the oldest or newest delivery; it's a blend of all of them. The calculation is simple: divide the total cost of all goods available for sale by the total number of units.

Finally, the Specific Identification method is the most precise but also the least common. It's used only when you can track the exact cost of each individual item from the moment you buy it to the moment you sell it.

This is really only practical for businesses with unique, high-value items—think of a car dealership tracking vehicles by VIN, a jeweler tracking specific diamonds, or an art gallery selling one-of-a-kind paintings. It gives you a perfect match of costs to revenue, but it's completely impractical for most manufacturers dealing with high volumes of identical parts.

Theory is one thing, but seeing how these inventory valuation methods play out with real numbers is where the rubber meets the road. Let's walk through a practical example to see just how different the financial picture can look.

We’ll use a fictional Tier-1 supplier we'll call ‘ComponentCo.’

ComponentCo buys and sells a specific high-tensile bolt. Like any real-world part, its purchase price fluctuates throughout the quarter. We're going to track its inventory buys and then see what happens to the books after a big sales push.

This is where you'll see how FIFO, LIFO, and Weighted Average Cost (WAC) can take the exact same business activity and produce wildly different financial outcomes.

The Scenario: ComponentCo's Quarterly Activity

First, let's lay out the inventory data for the quarter. ComponentCo started with some bolts on hand and made three more purchases before the quarter ended.

Inventory Activity:

- Beginning Inventory: 1,000 units @ $1.00 each = $1,000

- Purchase 1 (Jan 15): 1,500 units @ $1.10 each = $1,650

- Purchase 2 (Feb 20): 2,000 units @ $1.25 each = $2,500

- Purchase 3 (Mar 10): 1,200 units @ $1.40 each = $1,680

That gives us a total of 5,700 units available for sale for the period, with a total cost basis of $6,830.

Now, let's say ComponentCo sells 4,000 units during the quarter. The million-dollar question is: which costs do we match against that sale? This is where your choice of accounting method changes everything.

FIFO Calculation: First-In, First-Out

With FIFO, we assume the first bolts we bought are the first ones we sold. Think of it like a grocery store rotating its milk—sell the oldest stock first. We'll peel off our inventory costs starting from the top.

Here’s how we calculate the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) for those 4,000 units:

- From Beginning Inventory: 1,000 units @ $1.00 = $1,000

- From Purchase 1: 1,500 units @ $1.10 = $1,650

- From Purchase 2: 1,500 units @ $1.25 = $1,875

We only needed 1,500 units from that second purchase to hit our 4,000-unit sales total. Add it all up, and the COGS is $1,000 + $1,650 + $1,875 = $4,525.

The inventory left on the shelf consists of the newest, most expensive parts:

- Remaining from Purchase 2: 500 units @ $1.25 = $625

- From Purchase 3: 1,200 units @ $1.40 = $1,680

- FIFO Ending Inventory Value: $2,305

LIFO Calculation: Last-In, First-Out

Now let's hit rewind and run the numbers using LIFO. Here, we assume the newest units are the first ones out the door. This is often used for tax planning when costs are rising, as it matches higher, more recent costs against your revenue.

To find the COGS for the 4,000 units, we work backward from our most recent buy:

- From Purchase 3: 1,200 units @ $1.40 = $1,680

- From Purchase 2: 2,000 units @ $1.25 = $2,500

- From Purchase 1: 800 units @ $1.10 = $880

We used up the last two purchases completely, then dipped into the first purchase for the remaining 800 units. The total COGS comes out to: $1,680 + $2,500 + $880 = $5,060.

What’s left in our inventory? The oldest, cheapest units.

- From Beginning Inventory: 1,000 units @ $1.00 = $1,000

- Remaining from Purchase 1: 700 units @ $1.10 = $770

- LIFO Ending Inventory Value: $1,770

Weighted Average Cost Calculation

The WAC method skips the layers and just smooths everything out. It’s ideal when all your parts are identical and mixed together in a single bin—it’s impossible to tell the old from the new anyway.

First, we find the blended average cost for a single unit:

- Total Cost of Inventory: $6,830

- Total Units Available: 5,700

- WAC per Unit: $6,830 / 5,700 units = $1.1982 per unit (approximately)

With that number, the rest is simple multiplication:

- COGS: 4,000 units sold * $1.1982 = $4,792.80

- Ending Inventory: 1,700 units remaining * $1.1982 = $2,036.94

The numbers don't lie. From the exact same business activity, we've produced three different COGS figures and three different ending inventory values. LIFO results in the highest COGS and lowest inventory value, while FIFO shows the opposite.

This side-by-side comparison makes the financial impact crystal clear. Your accounting method directly changes your reported profitability and the value of assets on your balance sheet. That’s why picking the right one isn’t just an accounting task—it’s a critical business decision.

The Strategic Impact on Taxes and Financial Reports

This is where the rubber meets the road. Picking an inventory valuation method is far more than just a box-ticking exercise for the accounting department. It's a strategic financial lever that directly shapes your tax bill, reported profits, and the story your balance sheet tells investors, lenders, and stakeholders.

Understanding these trade-offs is crucial for any manufacturer. In an environment of rising costs—a reality every OEM and Tier-1 supplier knows well—your choice between LIFO and FIFO has real, tangible consequences for your cash flow.

How Valuation Shapes Your Tax Strategy

When material costs are climbing, LIFO becomes a powerful tool for managing your tax exposure. By matching your most recent, higher-cost purchases against current sales, LIFO inflates your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). This, in turn, shrinks your reported gross profit.

A lower taxable income means a smaller check written to the government. For a capital-intensive business, this isn't just a paper-saving; it's a real cash-flow advantage. That money can be pumped right back into operations, new equipment, or R&D.

FIFO, on the other hand, does the exact opposite. It matches older, lower-cost inventory against revenue, which makes your reported profits look bigger and, as a result, increases your tax liability. This strategic fork in the road is a huge reason why LIFO is still a popular choice for U.S.-based companies working under GAAP.

The decision is a classic strategic trade-off. LIFO can improve immediate cash flow by deferring taxes, while FIFO can present a more profitable picture to the outside world—but at the cost of a higher tax payment today.

The Balance Sheet and Investor Perception

While LIFO is great for the tax man, FIFO often makes a company look stronger on paper. During periods of inflation, FIFO results in a higher ending inventory value on your balance sheet because the items left on the shelf are valued at the most recent, higher prices.

This creates a few positive ripple effects on your financial reports:

- A Stronger Asset Base: A higher inventory value beefs up your total asset figure, making the balance sheet appear more robust.

- Higher Reported Profits: As we covered, lower COGS leads to higher net income, signaling strong profitability to investors.

- Improved Financial Ratios: Key metrics like working capital and the current ratio look healthier, which can be critical when you're looking for financing or trying to satisfy loan covenants.

This financial narrative is especially important when you're talking to lenders or courting investors. A company using FIFO can appear more profitable and asset-rich, which could help secure more favorable credit terms or a higher business valuation.

The ripple effect of your valuation method extends to key performance indicators, like mastering inventory turnover ratio calculation, which reveals how efficiently you’re selling through stock. A choice like FIFO, which can inflate inventory value, will definitely have an impact on that ratio.

The Real-World Financial Difference

We're not talking about small potatoes here. During periods of sustained inflation, the difference between these methods can be massive. For example, in a 5%–10% annual inflation scenario, FIFO can produce gross profit margins that are 3–8 percentage points higher than LIFO for businesses with moderate inventory turnover.

That margin difference translates directly into tax impacts. A company with $500 million in sales could see its taxable income shift by millions, leading to immediate tax deferrals of over $1.5 million per year just by using LIFO.

Ultimately, the right choice also hinges on your total cost structure. You need a crystal-clear understanding of every cost component, which is why so many of our clients at Wolverine Assemblies focus on https://www.wolverine-llc.com/blog/cutting-costs-without-cutting-corners-the-role-of-landed-cost-optimization to get the full financial picture before locking in these key decisions. The best inventory method is the one that aligns your accounting with your core financial and operational strategy.

Integrating Valuation Methods into Your ERP System

Your Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system is the central nervous system of your entire manufacturing operation, but it’s only as smart as you tell it to be. Choosing an inventory valuation method on paper is one thing; making it work flawlessly inside a system like Plex requires real-world planning and execution.

The goal is simple: make sure the digital ledger in your ERP perfectly mirrors what’s happening on your warehouse floor and in your financial statements.

Successfully integrating your chosen valuation method is much more than a one-time settings change. It demands a clear strategy that aligns your software with your physical warehouse processes. For instance, if you choose FIFO, your ERP must be configured to pull costs from the oldest inventory layers first. But just as importantly, your warehouse team needs to be trained on physical stock rotation to match that logic—ensuring older parts are actually used before newer ones.

Aligning Digital Settings with Physical Reality

The most common point of failure is a disconnect between the ERP setup and what's actually happening out on the floor. A system set to FIFO is useless if your team is just grabbing the most convenient pallet, which happens to be the one that just arrived. This mismatch creates inaccurate financial statements and massive compliance headaches down the road.

To prevent this, your implementation plan has to cover three key areas:

- System Configuration: This is step one. You have to set the correct cost flow assumption—FIFO, LIFO, or Weighted Average—within your ERP’s inventory module. This dictates how the system automatically calculates COGS and ending inventory value.

- Data Migration: When you switch systems or methods, historical inventory data must be moved over perfectly, with each layer of inventory assigned its proper cost. One mistake here can corrupt your financial data for years to come.

- Process Training: Everyone—from purchasing and warehouse staff to the accounting team—needs to understand how their daily actions impact inventory valuation. This means clear procedures for receiving, put-away, and picking that support your chosen method.

A properly configured ERP doesn't just record transactions; it enforces your accounting policy. It becomes the single source of truth that guarantees consistency between your physical inventory and your financial reports.

Avoiding Common ERP Implementation Pitfalls

Implementing or changing inventory valuation techniques in an ERP is a delicate process where tiny mistakes can have huge consequences. One of the biggest pitfalls is overlooking whether the system can even handle your chosen method effectively. Not all ERPs handle LIFO well, for example, especially if they’re designed for markets where IFRS standards (which don't permit LIFO) are the norm.

Another frequent misstep is failing to test the configuration thoroughly. Before you go live, you need to run simulations with real-world data. Verify that the system is calculating COGS and valuing inventory exactly as you expect. This one step can catch costly errors before they wreak havoc on your live financial data.

By understanding the critical role of your ERP, you can turn it from a simple record-keeping tool into a strategic asset. To dig deeper, you can learn more about what an ERP system is in manufacturing and how it powers modern supply chains. This knowledge is key to making sure your digital infrastructure truly supports your financial and operational goals.

How to Choose the Right Valuation Method for Your Business

Picking the right inventory valuation technique isn’t just an accounting chore. It's a strategic decision that needs to mesh with the reality of your business operations. After breaking down the different methods, it all comes down to a few key things: your industry, what your financial goals are, and the economic winds you're sailing in.

Think of it like picking the right tool for a specific job on the factory floor. You wouldn’t use a hammer to turn a screw. You have to look at what you’re selling, your tax strategy, and how you want your company’s financial health to look to the outside world. This choice hits your bottom line and your operational efficiency directly.

Matching the Method to Your Business Model

The best place to start is with your inventory itself. The type of products you handle will often point you straight to the right method.

For unique, high-value items: If you’re building custom machinery or any product where each unit is distinct and carries a high price tag, Specific Identification is really the only way to go. It’s more work, sure, but it gives you dead-on cost accuracy, which is critical for tracking profit on those big-ticket sales.

For perishable or tech-sensitive goods: When you’re dealing with products that have an expiration date or can become obsolete overnight (think electronics), FIFO is the most logical choice. It makes your accounting cost flow match the necessary physical flow of goods—getting the oldest stock out the door first.

For tax planning in the U.S.: During times of rising costs, LIFO can be a powerful tool for deferring taxes. By expensing your newest, most expensive inventory first, you lower your reported profits and, in turn, your tax bill. That frees up immediate cash flow.

Ultimately, the best method gives you a clear and accurate picture of your profitability while backing up your strategic goals. It should reflect economic reality, not hide it.

Final Considerations for Your Decision

Beyond just the type of inventory, think about your company's bigger picture. If you're looking for investors or a bank loan, FIFO's tendency to show higher profits and a stronger balance sheet can be more attractive to outsiders. On the flip side, if maximizing your day-to-day cash flow is the top priority, LIFO's tax benefits are tough to beat.

This choice also directly impacts your operations, influencing everything from your warehouse layout to your team's daily workflow. Making sure your accounting method works in harmony with your physical operations is key, a topic we cover more in our guide to effective stock and replenishment strategies. To take it a step further, proper implementation often comes down to the right tools, so it's worth reading up on finding the best inventory management software.

By weighing these factors carefully, you can land on the inventory valuation technique that truly serves your business.

A Few Common Questions, Answered

Even when the concepts are clear, putting inventory valuation into practice brings up some real-world questions. We hear these a lot, so here are some straightforward answers.

Can a Company Switch Its Inventory Valuation Method?

Yes, but it's a big deal. You can't just flip-flop between methods to make your numbers look better.

Under U.S. GAAP, you have to formally justify why the new method is a better fit for your business. This usually means restating your previous financial statements to reflect the change, which is a major undertaking. If you're moving away from LIFO, you'll also need to get the green light from the IRS. Consistency is a cornerstone of accounting, so regulators want to see a legitimate business reason, not just a short-term tax play.

How Does Inventory Valuation Affect Business Loans or Investments?

Your choice here directly shapes how banks, investors, and potential partners see your company’s financial strength. It tells a story.

During times of rising costs, FIFO makes your profits and balance sheet look stronger because your remaining inventory is valued at newer, higher prices. To a lender, this can look more appealing. On the flip side, LIFO reports lower profits, which can lower your tax bill and improve cash flow.

The bottom line is this: lenders see higher asset values under FIFO as better collateral, while the improved cash flow from LIFO's tax benefits can also be seen as a sign of prudent financial management.

A savvy investor will know how to read between the lines, but that first impression definitely counts.

Must the Physical Flow of Inventory Match the Accounting Method?

Nope. This is a common point of confusion. The physical movement of your goods doesn't have to mirror your accounting method.

For example, a warehouse team can follow a "first-in, first-out" process for practical reasons—like preventing spoilage—while the accounting team uses the LIFO method to calculate the cost of goods sold. Your valuation method is an accounting choice about cost flow, not a strict operational rule for your warehouse.

That said, aligning the two often makes things simpler. For perishable goods or electronics, matching the physical flow to the FIFO cost flow is just good sense. It keeps things straightforward and minimizes the risk of inventory becoming obsolete.

Ready to stabilize your supply chain and streamline your assembly processes? The team at Wolverine Assemblies, LLC has the expertise and infrastructure to help. Contact us today to discuss your project.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

.png)